UFC and Women’s MMA: Star power vs Staying power

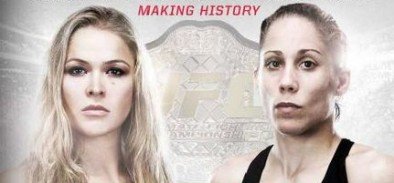

It’s rare that an MMA fighter’s face makes it into any sports publication, but as the spearhead of a new movement within the fight world, Ronda Rousey is all over the place. It’s odd to talk about Women’s MMA, or WMMA as “new” considering how long it’s been around, but main stream acceptance has been hard to come by for these ladies, and continues to be a struggle leading up to what should be its first major title bout.

It’s rare that an MMA fighter’s face makes it into any sports publication, but as the spearhead of a new movement within the fight world, Ronda Rousey is all over the place. It’s odd to talk about Women’s MMA, or WMMA as “new” considering how long it’s been around, but main stream acceptance has been hard to come by for these ladies, and continues to be a struggle leading up to what should be its first major title bout.

There are many questions for the UFC concerning their foray into WMMA, with their sincerity and managerial abilities laying at the forefront. Is this a cash grab by the UFC, riding a media wave around Rousey? If so, will they let it run its course, or put in the time and energy necessary to grow WMMA as a viable sport in the eyes of both hardcore and casual fans? This is a lofty question, and to get our answers we’ll need to look at the foundation of WMMA, whose roots are older than you might realize.

A Short History of Women in MMA:

There is no woman’s MMA Hall of Fame, with most of the pioneers of the sport lost in obscurity, yet WMMA really started shortly after MMA itself in the mid nineties. Largely used as an intermission in a time when MMA was almost entirely tournament based, WMMA fighters were composed of a similar stock to their male counterparts. High school wrestlers and tough woman competitors largely made up the US WMMA scene, while judoka formed the backbone of Japanese WMMA in the same era. This was before MMA fighters “cross-trained” disciplines, and while fighters were rarely technically pleasing on either side of the gender line, Male MMA was a grueling and honest affair.

For WMMA, with so few serious female competitors, the early scene was more spectacle than anything else. Decorated wrestlers and amateur boxers were typically left fighting the girlfriends of fighters on the card, whom often had literally no fight experience outside watching from the sidelines. This led to a lack of real competition, which kept women who could develop into strong fighters of their era facing a wave of untrained fighters. With no money in the sport and no interest from the fans to build a serious WMMA league in the US, early WMMA pioneers either left competition entirely or went to fight in Japan, which has held onto its WMMA roots the entire time. MMA plunged into the shadows and WMMA along with it.

As MMA transformed from a blood sport into a legitimate competition and Zuffa grabbed up the reins of the UFC, women once again could step into the cage, but the damage was already done. Without a path to follow from previous generations and without any tradition of WMMA left in the US, the sport had to restart. Once again, high school wrestlers, judoka and the girlfriends of fighters were thrown into the cage.

This was a double-edged sword though, as while women had a place to fight again, the bar set by the men was in the clouds at this point, leaving women fighting almost unbearable to watch in comparison to other matches on the card. The sport became a series of squash matches, as seasoned fighters stomped the untrained local talent, once again with nowhere to go and no money to make this a career. History could have repeated itself if not for a pair of fledgling companies that had the cash and desire to make WMMA a reality in the US once again.

The short-lived EliteXC was flawed from the beginning, yet they oddly treated WMMA with far more care than their short-sighted matchmaking among the men. Using their contacts in the boxing world and grabbing every female fighter plying their trade in a legitimate MMA gym, EXC staged the first WMMA fight on a major cable network, putting the stunning Gina Carano in the spotlight against WMMA veteran Julie Kedzie on Showtime. In what was the best bout of the night, the two went to war and set the tone for the new WMMA, which Strikeforce then picked up when EXC folded several years later. With the world paying attention for once, WMMA was back, and it was on the ladies’ shoulders to keep us entertained.

Where Women Stand Now:

With other organizations having picked up a stable of female fighters, women have been doing better than ever working their craft in the cage, yet there’s still a lot of work to be done. WMMA’s greatest obstacle has always been a lack of a talent pool, as few females are willing to put their looks on the line to compete in an oftentimes brutal sport. This talent pool doesn’t just affect matchmaking, but goes deep into the core of their training as well.

Even into the early part of the EXC/Strikeforce days, it would become immediately apparent that some women hadn’t trained properly for MMA, as sheer terror would take over the moment they’d been struck. Being hit in the face for the first time can be a life-altering experience, and to have that experience come inside the professional cage rather than in training showed how much difficultly women have had finding real training. The fact of the matter is, most MMA gyms don’t have more than one female, and males aren’t willing to go hard in the gym against the fairer sex.

Looking at the UFC as a sort of chronograph, with UFC 1 being blood sport with no rhyme or reason and UFC 100 being a well-oiled machine, WMMA is around UFC 35. Women know what works in the cage and are just now getting the money they need to keep fighting and draw other females in. Gyms are more accepting of females and there are enough females in MMA hotbeds throughout the country that small regional shows can regularly throw a couple of WMMA bouts onto the card and not have them be cringe worthy filler, but rather part of the show at a whole.

This is a critical time for WMMA, as the support of large organizations being pulled out now would kill the movement as a whole, and with UFC being the largest, they have the power to do the most good, and the most harm. This is a time for growing, but can the UFC do it justice, or just burn it out for profit?

Forming a Division

We’ve had the luxury of seeing this process several times as far as men are concerned, most notably in KOTC and WEC, where their Feather and Bantamweight divisions were among the first in the nation. A division begins with a pool of talent almost set to a rapid boil with massive turnover initially. Often someone floats to the top and stays firm among the group of contenders, but ranking fighters in a new division proves almost impossible initially. Only after years of stacking the division with the best of the best and flushing out the rest do you have a solid division with a definitely bottom, middle and top-tier.

This pattern has worked well throughout the history of the sport, and the UFC has made it the standard operation procedure to give a fighter the boot after two losses in four fights. In divisions like Lightweight and Welterweight, ripe and bursting with talent, this has made room for new and exciting fighters while giving mid-level battlers a steady paycheck for an entire career. Yet, this formula requires that massive talent poll to operate properly, and the folly of this practice has been seen in the Heavyweight and Flyweight divisions.

In these divisions where the talent pool isn’t as deep; Heavyweight athletes trending towards basketball and football while Flyweights are structurally difficult to come by, we’ve seen a stagnation and difficulty building a foundation respectively. The policy of booting a fighter for two losses simply doesn’t work when there’s no one better to replace him, and looking at the rosters of these two divisions, we see they’re lacking a real bottom rung.

For WMMA, this has long been the issue, and Zuffa’s current practices seem to be more of a hindrance than a help as WMMA moves to new heights. The fact of the matter is, most women in MMA don’t have stellar records, especially considering the necessity for fighting across sometimes 30lbs worth of weight classes. If WMMA is going to develop inside the UFC, it can’t afford to throw away fighters after losses, but invest in its own product and the future of WMMA itself.

By keeping fighters whom entertain and perform despite losses, they keep that fighter not only in the cage competing, but also in the gym to help budding female fighters make their way into the cage themselves. A steady paycheck for female fighters means more female fighters and more talent. Immediate firings after tough losses mean demoralized fighters and no development throughout the division.

Ronda Rousey, Then Everyone Else

Every division needs a star to draw attention, and this incarnation of WMMA has Ronda Rousey as its standard-bearer, whom the UFC expects to be a major draw. With the amount of media attention she’s received for her Olympic involvement, string of armbars, and willingness to discuss sex and pose “nude”, it stands to reason the UFC gets more than a few PPV buys from the blond judoka’s name on the marquee.

Yet, if stars are fleeting in the world of male MMA, WMMA royalty depart even quicker. Original queen Gina Carano came and went in a matter of a couple of years to the allure of movies, which pay more and are less work than MMA ever will be. WMMA will also see women depart to start families, which cut years out of their fighting primes and can prevent them from ever coming back to the fight game.

It’s easy to draw the parallel from Rousey to Carano, and if history repeats itself, Rousey will be off making movies while this division is still in that “rapid boil” process. Thus lays the folly in basing a division on someone who could leave at any moment and leave a faceless division full of former contenders. If the UFC is sincere about making a run in WMMA, they need to put an emphasis not just on Rousey, but on everyone in the division.

In the grand scheme of things, Carano had no lasting effect on the sport, yet her opponent on that fateful night WMMA hit Showtime is still around. Julie Kedzie still fights and trains female fighters, while also doing commentary for the all-female league Invicta. Having put the work in after that spotlight went out and keeping to the grind building a sport, rather than a paycheck, she’s been more important to WMMA than any amount of Carano’s and Rousey’s.

A successful division needs its stars, just as much as it needs its gatekeepers, mid-carders, bottom feeders, can crushers and every station a fighter can hold. Divisions aren’t singular enterprises, and the success of WMMA rests not only on how well they promote Rousey, but how they promote her opponents and placing exciting fights where people can actually see them. While WMMA will survive with or without the UFC, they hold the key to ultimate acceptance by fans and could catapult them into that next level of success.

From someone who’s followed the sport of MMA from its beginnings, through good and bad; Ladies, you’ve come a long way, now let’s go even further.